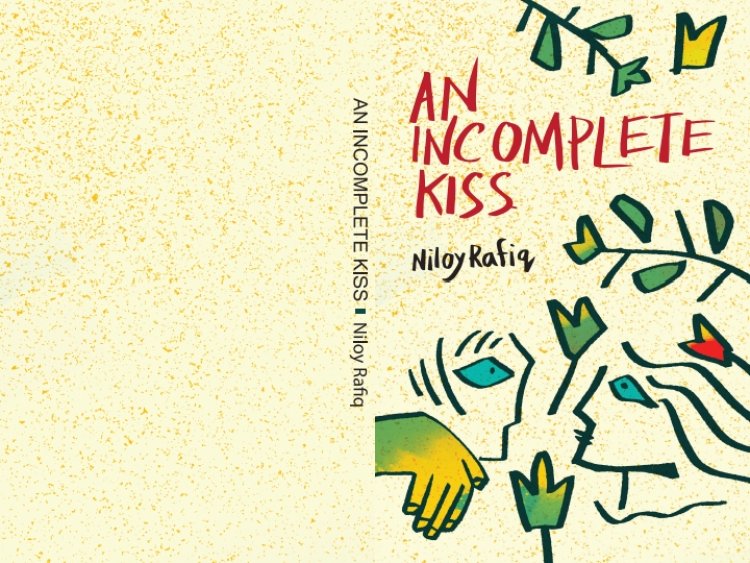

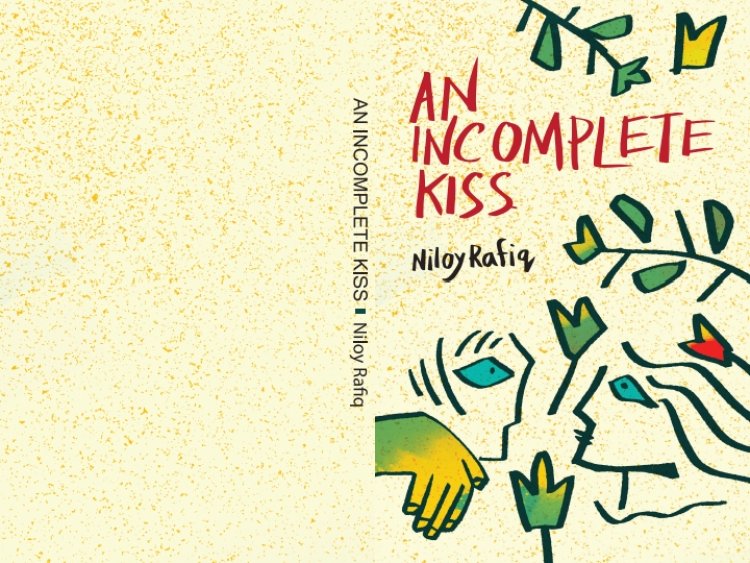

A Lyrical Odyssey Through Memory and Resistance: A Review of Niloy Rafiq’s An Incomplete Kiss

Gausur Rahman

Niloy Rafiq’s “An Incomplete Kiss” emerges as a luminous constellation of poetic brilliance, weaving a rich tapestry of Bengali sensibilities with universal themes of memory, socio-political resistance, and a profound communion with the natural world. The translated collection reveals a poet of depth, whose lyrical voice navigates the intricacies of human experience with both tenderness and ferocity. While the translations occasionally falter, encumbered by grammatical inaccuracies and awkward phrasing that dilute the resonance of Rafiq’s original intent, the poet’s poetry shines through, offering readers a transcendent journey through longing, rebellion, and spiritual reverie.

At the heart of Rafiq’s poetry lies a poignant engagement with memory, often imbued with an aching sense of incompleteness that resonates across cultural boundaries. In the titular “An Incomplete Kiss,” the lines “The words are flat in the cover of memory / Where the marks of incomplete kisses are left” encapsulate a yearning for wholeness, a motif that reverberates through the collection.

Similarly, “The Nose Pendant” evokes nostalgia with “Opening my eyes, I search still the nose pendant / Behind the clouds, in the cover of my memory,” where the pendant symbolizes a lost cultural tether, shrouded in recollection’s haze. “Gone Elsewhere” extends this theme, as seen in “Drawn by the navel, the beauty has gone away elsewhere / The map shivers in winter with the song of birds,” where the shivering map suggests a dislocation of identity.

However, the phrase “has gone away elsewhere” is grammatically redundant—correctly rendered as “has gone elsewhere” would suffice.

The sensory imagery of “I collect oysters from the sea shore / Everlasting happiness, being drawn by the earth” infuses the poem with tactile longing, yet “sea shore” should be “seashore” for grammatical consistency. “My Heart Aches For You” deepens this theme with “The dreamy heart rings with the song: / ‘My heart aches for you!’” where the ache is both personal and cosmic, mirrored by “Southern breeze wipes out the dusts of innumerable stars.” The plural “dusts” is incorrect—“dust” as an uncountable noun would be appropriate. “An Apple Afternoon” further explores this with “Inside a divorced secret purse in the city / A handsome dunce merchant weaves dreams,” suggesting a fragmented memory, though “divorced secret purse” feels awkward, potentially a mistranslation of a more nuanced Bengali metaphor.

This preoccupation with memory intertwines with socio-political commentary, most strikingly in “The Burning Torch,” where “People in burnt letters on the Chicago streets / Eighteen or twenty working hours, / Labour sucks blood from body” portrays the visceral toll of exploitation. The rallying cry, “A fragrantly united voice calls for a movement demanding the dues / Bullets to the brave march,” juxtaposes hope with violence, culminating in “A torch of light in the memorable history of May Day.”

Yet, the phrase “Victory Lamp” in “The harvest of hard work in the hands of Victory Lamp” is awkwardly phrased, lacking a definite article or clearer metaphor, disrupting the rhythm. “Unaddressed” complements this critique with “The clamour of clouds on the banks of destiny / The dead soul wakes up in the shore of ignorance,” suggesting collective disorientation, though “wakes up in the shore” should be “wakes on the shore” for precision. “Mathin’s Victory” introduces a narrative of resilience with “Dhiraj is written in history with deceitful eyes / Mathin’s victory in starving to death,” portraying a triumph born of suffering, though “deceitful eyes” feels ambiguous, and the phrase might benefit from clearer context. “The Blind Light” offers a stark socio-political allegory with “The habitat of fishermen is a void and the sea is forbidden / The scarcity sets happily while / The warehouse of food is on fire,” addressing systemic deprivation, though “sets happily while” is grammatically awkward—correctly “sets happily as” would improve clarity perfectly. “The Saltpit” echoes this with “Will the soil get back the lost seedbed? / Drought in its own separation the hide and seek trees,” a metaphor for environmental and cultural loss, though “the hide and seek trees” lacks a preposition, correctly “the hide-and-seek trees.”

Rafiq’s affinity for nature and spirituality, a hallmark of Bengali poetry, permeates his work with a Tagorean reverence. “Clouds In Front” offers celestial imagery in “The spring sun is flying, the tide is high / The wings of the body are embodied in the heaven’s hair-parting,” blending the earthly with the divine, though “are embodied” is redundant—“are entwined” would enhance flow.

The mythological “Pulsirat, the river of the dead” adds depth, yet the literal “heaven’s hair-parting” obscures the original metaphor. “Gone Elsewhere” echoes this with “Heavy fog makesthe life cycle a disaster / The future victorycounts time by the scent of sunflowers,” where “makesthe” and “victorycounts” are typographical errors, correctly “makes the” and “victory counts,” reflecting careless transcription. “The Ribs of Chest” further enhance this theme with “The old mud house is a glimpse of the industrial life / The words are the scented branches of the seed-bearing trees,” though “roots re divided” is a misprint, likely “roots are divided.”

“The Dream Drunkard” introduces a mystical dimension with “Rumi’s ambrosiac wine is in the forest of birds / Time stands still on the carriage in the Jhautla crossing,” invoking the Sufi poet Rumi, though “ambrosiac” is a questionable adjective—“ambrosial” would be more fitting. The line “The countenance of cloud is a secret poison” contains a grammatical error, as “cloud” should be plural or preceded by “the,” correctly “The countenance of the cloud.” “The Saltpit” brings a visceral connection to nature with “The infatuation of the sun like a water lily river lifetime end / The body wrapped with a cold mat,” though “lifetime end” is awkwardly phrased—perhaps “life’s end” was intended. “An Apple Afternoon” evokes a surreal natural imagery with “Flowers bloom like shadows in the unknown space; / The soul is dead, The life line is a procession of chariots,” where the capitalization of “The” is inconsistent, suggesting an editorial oversight.

Stylistically, Rafiq employs dense, evocative imagery and a rhythmic cadence reminiscent of oral traditions. Metaphors like the “gold coin smile” in “An Incomplete Kiss” or the “fragrantly united voice” in “The Burning Torch” enrich the text, yet translations falter. In “The Nose Pendant,” “Two artists are face to face on an ancient map” lacks a preposition, such as “facing each other,” rendering it vague. “Unaddressed” introduces “A trickery of balloon in the stream of time,” where “trickery” is singular but lacks agreement with “balloon,” suggesting “trickeries” or “a trickery with balloons.” The line “Who himself does not even know where the address is!” uses “himself” redundantly—“Who does not even know where the address lies” would be more elegant.

“My Heart Aches For You” presents “Draw water windows with the brushes of sounds,” where “water windows” is ambiguous and possibly a mistranslation, potentially intending “watery windows” or “windows of water.” “Mathin’s Victory” includes “The water turned blue and blood red!” where the exclamation feels forced, and “blood red” should be hyphenated as “blood-red” for grammatical correctness. “The Saltpit”’s “Light and shadow sand particles silent sea!” is a run-on phrase lacking punctuation—“Light and shadow, sand particles, silent sea!” would provide clarity. “The Blind Light”’s “You can see tet it’s a blind light in a city of dumbs” contains a typographical error, “tet” instead of “that,” and “dumbs” should be “the dumb” for grammatical accuracy. “An Apple Afternoon”’s “Salty tamarisks are wrapped in sound under a cover of light / Golden village of the root is an ambrosia inside” uses “ambrosia” as a noun but feels awkward—perhaps “ambrosial essence” would better capture the intended metaphor.

Cultural specificity, evident in references like the “Old Brahmaputra river,” “Krishnachura Road,” or “Jhautla crossing,” grounds the poetry in a Bengali milieu, yet may alienate readers without context. In “An Incomplete Kiss,” “The Old Brahmaputra river calls whom?” employs the archaic “whom” incorrectly—“who” would be appropriate in this case. “Gone Elsewhere”’s “May the immortal treeblossom in a bright light” contains a typographical error, “treeblossom” instead of “tree blossom,” and lacks an article, correctly “May the immortal tree blossom in a bright light.” “Mathin’s Victory” references “Patuar Tek,” a likely Bengali locale, but without annotation, its significance remains obscure. “The Saltpit”’s “Fragrance of tradition the craftsman in the black clouds / Smell of soil in the heart and water the refugee roots!” is evocative but grammatically disjointed—adding a conjunction, “Fragrance of tradition, the craftsman in the black clouds, / Smell of soil in the heart, and water, the refugee roots!” would improve coherence. The absence of contextual notes exacerbates this opacity, a missed opportunity to bridge cultural gaps.

Despite these flaws, Rafiq’s voice shines through, blending lyrical beauty with social awareness. “The Ribs of Chest” captures heritage’s tension with division, though “dialogues in the dark assassin” is grammatically incoherent, possibly intending “dialogues with a dark assassin.” “Unaddressed”’s “Immersed in a prayer in the palace of flowers / A chant of hymns at the door of death” evokes a spiritual journey, yet “palanquin of clouds is under the storm” should be “the palanquin of clouds is beneath the storm” for clarity. “The Dream Drunkard”’s “Draws water circles, the light of birds on the way to the stars” is poetically striking but grammatically awkward—“Drawing water circles, the light of birds guides the way to the stars” would enhance clarity. “The Blind Light”’s “The cunning fox steals hilsa fishes inside the ribs” uses “fishes” redundantly—“fish” would suffice, aligning with standard English usage.

Beyond these critiques, Rafiq’s poetry commands an effervescent brilliance that elevates “An Incomplete Kiss” to a realm of timeless artistry, a testament to his mastery of language and emotion. His ability to distill the ineffable—whether the ache of an unfulfilled kiss or the collective cry for justice—into crystalline imagery is nothing short of masterful. In “The Burning Torch,” the transformation of labor’s suffering into “A torch of light in the memorable history of May Day” is a testament to Rafiq’s skill in alchemizing pain into hope, a feat that resonates with the global canon of resistance poetry.

The delicate interplay of nature and spirituality in “Clouds In Front,” where “The spring sun is flying, the tide is high,” evokes a cosmic dance that transcends cultural boundaries, inviting readers into a pantheistic embrace that feels both ancient and eternal. “Unaddressed” further exemplifies this, with “A chant of hymns at the door of death” offering a hauntingly beautiful meditation on

mortality, where the spiritual and material converge in a moment of sublime clarity. “The Dream Drunkard” enchants with “A frenzy of music is reverberating in the Jhautla crossing,” weaving a spell of intoxication that mirrors Rumi’s mystical legacy, while “My Heart Aches For You” captures a tender longing in “Howrapt the sea is with elated uproars!”—a line that, despite its grammatical error (“Howrapt” should be “How rapt”), pulses with emotional authenticity. “Mathin’s Victory” celebrates resilience with “The high and low routes are the fragrance of love,” a metaphor that encapsulates Rafiq’s ability to find beauty amidst struggle. “The Saltpit” mesmerizes with “Misty saltpits a fair of lightning,” a vivid image that transforms desolation into a spectacle of nature’s power, while “The Blind Light”’s “The life story is a pendulum of dreamful ballad” offers a philosophical reflection on existence, blending the cyclical with the lyrical. “An Apple Afternoon”’s “The road is open, as far as you can go / I’ll search out an apple afternoon on my palm” is a tender promise of hope, where the “apple afternoon” becomes a symbol of renewal amidst despair.

Rafiq’s metaphors—the “gold coin smile,” the “scented branches of the seed-bearing trees”—are not merely decorative but revelatory, peeling back layers of human experience to reveal truths that linger long after the page is turned. His work, even through the veil of imperfect translation, radiates a luminous authenticity, positioning him as a poet of profound emotional and intellectual depth, whose verses deserve a place among the luminaries of modern poetry. Each poem in this collection is a delicate mosaic, where every word is a shard of light, refracting the complexities of the human soul with a grace that is both ethereal and grounded. Rafiq’s ability to traverse the spectrum of human emotion—from the quiet despair of “The Nose Pendant” to the fiery defiance of “The Burning Torch”—marks him as a bard of versatility, a weaver of dreams whose verses are as timeless as the rivers and skies he so vividly invokes.

“An Incomplete Kiss” is a testament to Rafiq’s ability to navigate the personal and collective, the local and universal, with a distinctly Bengali sensibility. The thematic depth—memory, resistance, and nature—offers a rewarding exploration, yet the translations are hindered by grammatical errors like “makesthe,” “re divided,” and “be perished,” alongside awkward phrasing such as “heaven’s hair-parting” and “Victory Lamp.” For readers willing to engage with its cultural nuances, the collection remains a poignant reflection of human experience, elevated by Rafiq’s poetic genius, though a refined translation would better honor his vision.

Prepared for publication by Angela Kosta