Relevance of Nazrul Studies

Dr. Md. Hasan Ali

Abstract

Kazi Nazrul Islam represents one of the most distinctive voices in Bengali literature, renowned for his rebellious spirit, humanism, and engagement with societal transformation. Through his poems, songs, essays, and other literary contributions, Nazrul provided a revolutionary perspective on literature, music, politics, and social justice. Under the oppressive rule of the British Empire, his works became the voice of the oppressed, inspiring a sense of national identity, courage, and independence among Bengalis. Even in contemporary Bangladesh, his ideals—rooted in freedom, equality, and human dignity—remain profoundly relevant. This paper examines Nazrul’s literary contributions in the context of national consciousness, humanistic values, Islamic heritage, and socio-political awakening. Through textual analysis, historical contextualization, and thematic interpretation, it demonstrates how Nazrul’s works continue to function as a counterforce against tyranny, injustice, and moral decay in society. The study argues that understanding Nazrul’s multifaceted contributions is essential for comprehending both historical and contemporary cultural dynamics in Bangladesh.

Keywords: Kazi Nazrul Islam, Bengali literature, rebellion, national consciousness, humanism, Islamic heritage, freedom, Bangladesh, colonial resistance, cultural identity

1. Introduction

Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam was far from an ordinary literary figure; he remains one of the most eminent poets of Bangladesh. While popularly celebrated as the “Rebel Poet,” he has been accorded the honor of National Poet in recognition of his unparalleled contribution to Bengali literature. His emergence coincided with a period when the people of the Indian subcontinent, under the oppressive rule of the British Empire, endured severe exploitation and sought liberation through independence movements. It was during this historical juncture that Nazrul composed seminal works, including Bidrohi (The Rebel), Proloyollash, Kheya Parer Taroni, as well as songs such as Shikol-Pora Chhal Moder Ei Shikol-Pora Chhal and Durgom Giri Kantar Maru, which inspired both the struggle for independence and subsequent generations of freedom fighters in Bangladesh.

Nazrul’s literary genius may be regarded as a unique gift, interwoven with the historical and cultural milieu of his era. A survey of Bengali literature indicates that, in contrast to the prevailing materialistic tendencies of his contemporaries, Nazrul’s work embodied a distinctive humanistic vision.^ Born on 24 May 1899 and passing on 29 August 1976 at 10:10 a.m. at PGI (present-day Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Medical University) (11 Jyoishtho 1306–12 Bhadra 1383 Bangla calendar), he lived for seventy-seven years and three months.^ Although he actively engaged in literary creation for only twenty-three years (1919–1942), he left an indelible mark on Bengali literature, demonstrating multidimensional talent and artistic versatility.

His extraordinary creative capacity, coupled with the richness of his life experiences, enabled him to infuse his works with aesthetic sophistication and revolutionary dynamism. This remarkable integration of life and art positioned Nazrul as a transformative figure in the evolution of modern Bengali literature, establishing a distinctive literary trajectory and contributing a historically significant literary foundation. Through his oeuvre, he challenged entrenched superstition and traversed all literary genres. Nazrul introduced revolutionary ideals into action, rebellion into youth, and harmonized them with Islamic principles, egalitarianism, and refined conceptions of love and morality. This enabled him to contribute meaningfully to a literary tradition that transcended religious and social boundaries.

Nazrul’s multifaceted identity encompasses not only poetry but also prose, drama, essays, translation, children’s literature, music composition, and lyricism. Yet, at his core, he remains a poet—a rebel poet and a poet of national consciousness. His intellectual and artistic development occupies a special position in the cultural and psychological landscape of Bangladesh. The following discussion examines the contemporary relevance of Nazrul studies in the context of his enduring legacy in the motherland.

2. Contextual Background

In analyzing Nazrul within the context of Bangladesh, the discussion inevitably intersects with the finer aspects of literature. Until now, there has been no comprehensive examination of the multifaceted realities of Bangladesh, its people, and its natural environment as they influenced Nazrul’s life and work. Existing studies have been minimal, fragmented, and largely superficial. Consequently, literary critique, artistic evaluation, assessment of talent, or discussions of relevance have not emerged as primary concerns; the focus has largely been limited to exploring how Nazrul’s creations impacted Bangladesh or served as a source of inspiration.

To address the question of why Nazrul remains relevant in contemporary Bangladesh, it is noteworthy that more than fifty years ago, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman brought the ailing poet to the country under the orders of the Government of India. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman foresaw that Nazrul would one day become highly pertinent to Bangladesh because he considered the poet a visionary exemplifying ideals. Upon arriving in Bangladesh during his childhood, Nazrul formed an intimate connection with its people and natural landscape. In subsequent years, the poet visited the country on various occasions for diverse reasons, residing in nearly twenty-five districts.

In 1926, Nazrul, accompanied by Abdul Qadir, came to Joydebpur and composed the poem Joydebpurer Pothe, which was later published in a periodical under the title Chandni Rate. On that day, within the confines of an inter-class room, he immersed himself in multifaceted waves of emotion, separation, and sorrow. Nazrul was a poet of passion, of emotion, of youthfulness, vitality, strength, and progress. He was a poet of love, humanity, beauty, and fraternity. Yet, the very ideals for which he had been brought to this country as a visionary remain largely unfulfilled to this day. The reasons that rendered Nazrul relevant in the past have now become exponentially more significant in the present.

3. Ideology of Life

When a country is tightly bound under oppressive rule, embracing the fundamental ideals of Nazrul’s poem Khoka’r Shadh becomes a duty for every citizen. The poet declares in this work:

"I shall be the morning bird,

I will awaken first in the flower garden."

Now is the time to rise with unstoppable momentum to build a state and society free from exploitation. Regardless of political affiliations, through national unity, it is necessary to harmonize with the poet’s voice and proclaim:

"Where is Genghis, Mahmud of Ghazni, where is Kalapahar?

Break open every lock and door of their temples!

Who places locks on God’s house, who dares seal it?

Every door shall remain open, strike with hammer and club!"

Historical evidence shows that figures like Genghis Khan or Mahmud of Ghazni, despite being irreligious or heretical, did not hesitate to wield hammers and clubs in temples of oppression. Yet, Nazrul calls for shattering the locks on God’s house and punishing those who assault Islam. The nation and system Nazrul envisioned were never realized, neither in India nor in Bangladesh. Nevertheless, he sowed the seeds of revolutionary potential among the laboring masses.

In the poem Kulimjur, while singing the songs of the downtrodden and awakening, the poet articulates in the language of struggle:

"The auspicious day is approaching,

Debts, long accumulated, must be cleared!

Those who shattered mountains with hammer and club,

Whose bones now lie along the path of cut mountains,

Those who served you, laborers and porters,

Those who bore dust upon their sacred bodies,

They are human, they are divine, sing their songs!

Upon their wounded chests rises a new dawn!"

‘New Dawn’ becomes a revolutionary reflection and symbol of the uprising of the oppressed. Here, the poet envisions the construction of a new society in opposition to the decayed old order, standing atop the ruins of tyranny, celebrating the triumph of a cultivated ideal. Nazrul emphasizes that mere movements alone cannot secure freedom; decisive action, including armed struggle if necessary, is required.

In Obhijan (26 July 1926, Narayanganj), he calls upon the seekers of liberation to embark on a mission to establish an ideal society, singing loudly at the threshold of dawn:

"Endure not so much injustice, O great one!

The oppressed cannot bear more, nor endure humiliation."

Nazrul depicts the awakening, struggle, and uprising of the oppressed in an unprecedented manner. The poet questions the injustice of a world where the natural bounty granted by Almighty Allah—the sky and fertile land—is at the disposal of tyrants:

"Who binds oppression with your gifted hands?

Whose laws chain my free movement?

Hunger and thirst exist, my life persists,

I too am human, I too am great!

Beneath me lies my tongue, this stiff neck!

I have torn the chains of my mind, yet the chains of my hands remain."

Here, he proclaims the eternal victory of freedom and unity in the uprising of the oppressed. Nazrul transcends sectarian Hindu-Muslim conflict, drawing inspiration from global struggles such as the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the rise of nationalism in Turkey. As Bangladesh’s National Poet, he embodies the profound critique of injustice and arbitrariness. While revolutionary storms were anticipated, he also raised songs of equality and secular ideals—principles that resonate in post-independence Bangladesh as a manifestation of resistance against colonial oppression.

4. The Supreme Sentiment of the Times

Although the rebellious ideology has been formally enshrined in Nazrul’s poetry and recitations, its relevance and impact continue to be profoundly felt, representing one of the era’s highest demands. Nazrul never enslaved himself to a particular political philosophy or ideological dogma. For those obsessed with promoting secularism, it is worth noting that his poem Qurbani (published in Muslim Bharat, Bhadra 1327) and compiled in Agnibeena, written in response to Tariqul Alam’s essay Aj Eid (Sabuj Patra, Shravan, 1327), does not align with Alam’s arguments but instead seeks to illuminate the true significance of sacrifice through a rhythmic six-beat meter.

For Nazrul, Qurbani is not mere killing; it manifests as “truth-holding” (Satya-graha) and the “unleashing of power.” In 1912, Mahatma Gandhi initiated his nonviolent movement and Satyagraha in South Africa in response to the humiliation of Black people. By 1919, during the Rowlatt Act protests in Champaran and Gujarat, and through 1920–22, the Non-Cooperation Movement reached its apex in India. Nazrul’s use of the term Satya-graha in Qurbani draws directly from these contemporary political struggles.

Nazrul consistently despised cowardice and timidity. He perceived Tariqul Alam’s essay as subtly endorsing passivity and, in response, asserted a more vigorous, uncompromising vision:

"The sound arises, far-reaching call—

Today is the sacrifice of the slaughter!

The heads of the martyrs are supreme today!

Is the Merciful not also fierce?"

Here, Nazrul emphasizes that mere prayers with raised hands are insufficient; decisive, vigorous action is also essential. The poet reinforces this with the command, “Byas! Chup khamosh rodan!”—using the Persian word khamosh to strengthen the injunction, silencing passive lamentation. The echoes of past sacrifices resound in the present crisis: “Today my strength rises: kill, give life, give head, give calf—listen.”

In Nazrul’s creative philosophy, the past is not commemorated solely for its own glory; it exists to invigorate the present, to realize truth and freedom. If the struggle demands battle, there is no fear; if blood is shed, so be it. While the path is neither simple nor easy, self-sacrifice and courage remain indispensable for achieving liberation and implementing justice.

4.1 Life Ideals and the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)

4.1 The Prophetic Ideal in Life

In the southwestern region of Asia, surrounded by deserts, seas, and oceans, lies an ancient and historically significant land, home to sacred cities that once hosted a diversity of Caldean, Semitic, Jewish, and Christian communities, each with their own idols and centers of worship. Amidst the moral degradation of his contemporaries, in this very land, the herald of humanity and the guide for all mankind, Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), was born in 570 CE. He awakened the spiritual and historical consciousness of his era with joy and purpose. Against the rigidity of religious orthodoxy, he established Islam in a manner universally applicable and beneficial to humankind.

Nazrul beautifully portrays the Prophet’s life—from childhood through adolescence and youth, to his death—in his poem Fateha-i-Dawaz Dahum, capturing the essence of the prophetic ideal:

"Nai ta-j

Tai la-j

O Muslim, adorn the date-palms!"

This poem addresses those who, claiming to represent the divine, indulge in human sacrifices or exalt themselves in positions of power while acting outside the divinely ordained order under the guise of religious tolerance, declaring war against justice. Nazrul, as a Muslim, neither endorsed rigid orthodoxy nor allowed his own faith to be diminished by opportunistic practices.

Through his poem Rokhkhaner Rakt, he delivers a direct and powerful critique of secularism, foreign oppression, and cowardly domestic authorities. In Proloyollash, he envisions the destruction of fascist tyranny and speaks words of hope to the youth for the dawn of a new era. In Bidrohi, he celebrates the refusal to submit before higher ideals, the explosion of individual personality, and the vow to erase the oppressor’s sword from the cries of the persecuted.

In Raktambaradharin Ma, Nazrul evokes the image of a goddess vanquishing demons, calling for the destruction of tyrants. Similarly, the poem Agomoni conveys the annihilation of false demonic armies and the triumph of righteous forces, though here Nazrul’s demons and gods symbolize human agents of oppression—those who commit violence, plunder, abductions, and injustice, thereby eroding morality.

In works such as Dhumketu, Kamal Pasha, Ranabheri, Shat-il-Arab, Kheya Parer Taroni, Qurbani, and Agnibeena, the poet celebrates the courage of truth, the spiritual and physical struggle for creative freedom, and the triumph of the fighting soul. These works stand as milestones, bearing testimony to historical shifts and the transformative power of revolutionary consciousness.

4.2 Symbolic Representation

The storm (jhor) is one of Nazrul’s most cherished symbols. To him, all forms of destruction—floods, famines, epidemics, and catastrophes—are subservient to divine command. Those who can shift the course of any storm in an instant represent injustice, oppression, and tyranny, which remain nothing but mere instruments of subjugation. Yet, Nazrul expresses the suffering of his motherland as a personal anguish:

"In this poisonous flute, my oppressed motherland has sounded twenty notes,

And upon me, the Creator has unleashed every form of cruelty and oppression."

Thus, on days of distress, there is no doubt that the call to revolution will strike from the depths of existence. Indeed, doubtlessness is a defining feature of Nazrul’s youth. In poems such as Sandhya (dedicated to the tax-levying forces and heroic leaders of Madaripur Peace Army, Bhadra 1306/1929), he illuminates the glory and vigor of his youthful self. Even after independence, he portrays the prolonged darkness of subjugation as twilight:

"At the eastern gateway, Sarbari awakens,

Ashamed that the sun has set in our cowardice,

I seek repentance for this great sin through the ages…

Will the twilight not pass?

How many lifetimes must one endure the debt of a single life?"

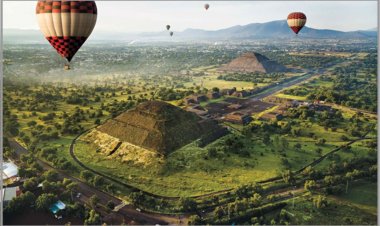

Here, Nazrul questions whether the long darkness will ever end. Will a new sunrise grace the fate of Bangladesh? Will the audacious, youthful energy of the nation dismantle the pyramid of arrogant oppressors? Undoubtedly, it will. History proves that even the most ancient monuments—like the pyramids of Egypt—can be destroyed by the force of youthful energy, laying the groundwork for new visions, flowering of life, and a pulse of peace. For this, a fearless, vigorous youth is indispensable—a force Nazrul embodied in his own creative life.

Today, those who seek youth merely in pleasure and desire experience only a shallow torrent of life. True youth, according to Nazrul, is the name of a new guiding light. Therefore, he celebrates youth with sublime imagery:

"Break the dam, let the flood of your life flow around,

Swing it in your breast, O youthful wave!

Let both banks, filled with stone, be carried away in the torrent.

Let it become fertile, let flowers and fruits bloom in harmony."

In Nazrul’s oeuvre, youth is synonymous with a fertile, vibrant life. He emphasizes this because the aged, the overly cautious, and the prudent can never truly embody the vitality of youth. Youth is repeatedly depicted in his poetry as streams, waves, tides, floods, and torrents—dynamic forces for creative action. Without harnessing this force, historical patterns of stagnation and decline recur, like the drowning of Pharaoh in the Nile.

Nazrul’s nationalism is often intertwined with revolutionary zeal. His poem Proloy-Shikha (1930), inspired by revolutionary poets Jatindra Mukherjee and Jatin Das, was confiscated by the government, along with another collection, Chandrabindu. This poem, however, represents his final published work in full health. Later, during his illness, Notun Chand and Maruvashkar were published, reflecting the revolutionary consequences of his initial defiance.

Nazrul’s poetry also manifests deep engagement with Islamic spiritual traditions and the political consciousness of the Muslim world. In Agnibeena, poems such as Kamal Pasha, Anwar, and Ranabheri reference Turkey, while Shat-il-Arab evokes Iraq, highlighting both subjugation and the yearning for freedom. In Kheya Parer Taroni, Moharram, and Qurbani, he celebrates the spiritual triumph of truth within Islam. In Bisher Banshi and Fateha-i-Dawaz Dahum, he chronicles the birth, life, and passing of the globally revered Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), capturing joy, sorrow, and exemplary ideals with careful attention and devotion. Through such imagery, Nazrul inspires readers with the prophetic ideal.

In Bhanger Gaan’s Shahidi Eid, the poet calls for total sacrifice in the struggle for truth. Across his works on Islam and the Muslim world or the Middle East, Nazrul awakens profound spiritual ideals, capable of energizing the present moment. The motif of chains (jingir) recurs as a symbol of oppression. In poems referencing past Islamic states or military heroes, such as Khaled, Chiranjib Jaglul, Amanullah, and Umar Farooq, he draws inspiration from the valorous heritage of Islam, establishing his works as some of the most significant in Bengali literary tradition.

5. Conclusion

Poet Kazi Nazrul Islam represents one of the most remarkable intellectual developments among Bengalis and stands as a supreme exemplar of Bengali creativity. The indelible mark he left in literature and music is a natural testament to the breadth and depth of his multifaceted genius. However, for those who seek to distort Nazrul under the guise of secular identity, the Nazrul revisionist initiative serves as a corrective. One must not diminish the divine wealth of the poet’s oeuvre with misrepresentation.

Nazrul’s extraordinary contributions span the state, social, cultural, and political spheres, as well as the religious and cultural heritage of his own faith. It is impossible for any commentator or scholar to fully capture the richness of his creative history in a short span of time. Engagement with Nazrul’s work should function as an unveiling of freedom itself—illuminating, emancipatory, and deeply inspiring.

References

Ali, H. (n.d.). Nazruler srishtite Bangladesher manush o prokriti. Dhaka: Bangla Academy.

Islam, R. (n.d.). Nazruler sahitya. Dhaka: Shubho Prakashan.

Mahmud, S. (n.d.). Nazrul sahitye puran prosongo. Dhaka: Bangla Academy.

Morshed, A. K. M. (n.d.). Rabindranath Nazrul o onnanno prosongo. Dhaka: Bad Comprint and Publication.

Banu, S. M. (2010). Samkali Bangla Shishu-Sahitya o Kazi Nazrul Islam. Dhaka: Nazrul Institute.

Alam, M. U. (2015, August 28). Nazrul keno prashongik. Samakal, p. 49.

Mondal, S. (2011, May 24). Ajo dui Banglay Kabi Nazruler prashongikota o jonopriyota amlan. Probhater Feri.

Khan, M. (2020, May 23). Nazrulcharcha o er prashongikota. Kaler Kantho, p. 71.

Prepared for publication by Angela Kosta

Moderator

Moderator